Chill is in the air and that means it’s time to turn your attention to year-end tax planning. While several clear strategies and tactics emerged during the first tax filing season under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), 2019 and subsequent years bring potential twists that must be considered, too. Let’s take a closer look at year-end tax planning strategies that can reduce your 2019 income tax liability.

Deferring Income and Accelerating Expenses

Deferring income into the next tax year and accelerating expenses into the current tax year is a time-tested technique for taxpayers who don’t expect to be in a higher tax bracket the following year. Independent contractors and other self-employed individuals can, for example, hold off on sending invoices until late December to push the associated income into 2020. And all taxpayers, regardless of employment status, can defer income by taking capital gains after January 1. Be careful, though, because by waiting to sell you also risk the possibility that your investment might become less valuable.

Bear in mind, also, that there may be other reasons that taking the income this year can be more beneficial. For starters, future tax rates can go up. It’s possible that income tax rates might increase substantially by 2021, especially for those with higher incomes, depending on 2020 election results. In any event, in 2026, the higher tax rates that were in place for 2017 are scheduled to return.

Moreover, taxpayers who qualify for the qualified business income (QBI) deduction for pass-through entities (that is, sole proprietors, partnerships, limited liability companies and S corporations) could end up reducing the size of that deduction if they reduce their income. It might make more sense to maximize the QBI deduction — which is scheduled to end after 2025 — while it’s available.

Timing Itemized Deductions

The TCJA substantially boosted the standard deduction. For 2019, it’s $24,400 for married couples and $12,200 for single filers. With many of the previously popular itemized deductions eliminated or limited, some taxpayers can find it challenging to claim more in itemized deductions than the standard deduction. Timing, or “bunching,” those deductions may make it easier.

Bunching basically means delaying or accelerating deductions into a tax year to exceed the standard deduction and claim itemized deductions. You could, for example, bunch your charitable contributions if it means you can get a tax break for one tax year. If you normally make your donations at the end of the year, you can bunch donations in alternative years — say, donate in January and December of 2020 and January and December of 2022.

If you have a donor-advised fund (DAF), you can make multiple contributions to it in a single year, accelerating the deduction. You then decide when the funds are distributed to the charity. If, for instance, your objective is to give annually in equal increments, doing so will allow your chosen charities to receive a reliable stream of yearly donations (something that’s critical to their financial stability), and you can deduct the total amount in a single tax year.

If you donate appreciated assets that you’ve held for more than one year to a DAF or a nonprofit, you’ll avoid long-term capital gains taxes that you’d have to pay if you sold the property and (subject to certain restrictions) also obtain a deduction for the assets’ fair market value. This tactic pays off even more if you’re subject to the 3.8% net investment income tax or the top long-term capital gains tax rate (20% for 2019).

What if you’re looking to divest yourself of assets on which you have a loss? Rather than donate the asset, the better move from a tax perspective is more likely going to be to sell it to take advantage of the loss and then donate the proceeds.

Timing also comes into play with medical expenses. The TCJA lowered the threshold for deducting unreimbursed medical expenses to 7.5% of adjusted gross income (AGI) for 2017 and 2018, but it bounces back to 10% of AGI for 2019. Bunching qualified medical expenses into one year could make you eligible for the deduction.

You also could bunch property tax payments (assuming local law permits you to pay in advance). This approach might, however, bring your total state and local tax deduction over the $10,000 limit, which means that you’d effectively forfeit the deduction on the excess.

As with income deferral and expense acceleration, you need to consider your tax bracket status when timing deductions. Itemized deductions are worth more when you’re in a higher tax bracket. If you expect to land in a higher bracket in 2020, you’ll save more by timing your deductions for that year.

Loss Harvesting Against Capital Gains

2019 has been a turbulent year for some investments. Thus, your portfolio may be ripe for loss harvesting — that is, selling under-performing investments before year end to realize losses you can use to offset taxable gains you also realized this year, on a dollar-for-dollar basis. If your losses exceed your gains, you generally can apply up to $3,000 of the excess to offset ordinary income. Any unused losses, however, may be carried forward indefinitely throughout your lifetime, providing the opportunity for you to use the losses in a subsequent year.

Maximizing your Retirement Contributions

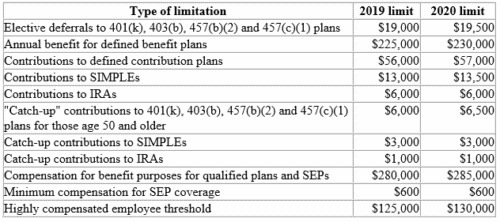

As always, individual taxpayers should consider making their maximum allowable contributions for the year to their IRAs, 401(k) plans, deferred annuities and other tax-advantaged retirement accounts. For 2019, you can contribute up to $19,000 to 401(k)s and $6,000 for IRAs. Those age 50 or older are eligible to make an additional catch-up contribution of $1,000 to an IRA and, so long as the plan allows, $6,000 for 401(k)s and other employer-sponsored plans.

Accounting for 2019 TCJA Changes

Most — but not all — provisions of the TCJA took effect in 2018. The repeal of the individual mandate penalty for those without qualified health insurance, for example, isn’t effective until this year. In addition, the TCJA eliminates the deduction for alimony payments for couples divorced in 2019 or later, and alimony recipients are no longer required to include the payments in their taxable income.

Factor 2020 Cost-of-Living Adjustments into your Year-End Tax Planning

The IRS recently issued its 2020 cost-of-living adjustments. With inflation remaining largely in check, many amounts increased slightly, and some stayed at 2019 levels. As you implement 2019 year-end tax planning strategies, be sure to take these 2020 adjustments into account in your planning.

Also, keep in mind that, under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), annual inflation adjustments are calculated using the chained consumer price index (also known as C-CPI-U). This increases tax bracket thresholds, the standard deduction, certain exemptions and other figures at a slower rate than was the case with the consumer price index previously used, potentially pushing taxpayers into higher tax brackets and making various breaks worth less over time. The TCJA adopts the C-CPI-U on a permanent basis.

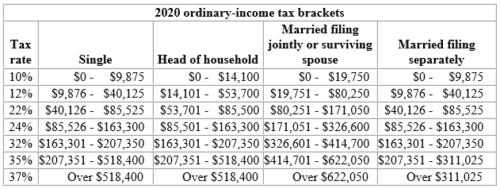

Individual Income Taxes

Tax-bracket thresholds increase for each filing status but, because they’re based on percentages, they increase more significantly for the higher brackets. For example, the top of the 10% bracket increases by $175 to $350, depending on filing status, but the top of the 35% bracket increases by $8,100 to $9,700, again depending on filing status.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) suspended personal exemptions through 2025. However, it nearly doubled the standard deduction, indexed annually for inflation through 2025. For 2020, the standard deduction is $24,800 (married couples filing jointly), $18,650 (heads of households), and $12,400 (singles and married couples filing separately). After 2025, standard deduction amounts are scheduled to drop back to the amounts under pre-TCJA law.

Changes to the standard deduction could help some taxpayers make up for the loss of personal exemptions. But it might not help a lot of taxpayers who typically itemize deductions.

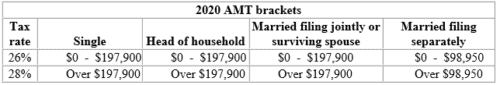

AMT

The alternative minimum tax (AMT) is a separate tax system that limits some deductions, doesn’t permit others and treats certain income items differently. If your AMT liability is greater than your regular tax liability, you must pay the AMT.

Like the regular tax brackets, the AMT brackets are annually indexed for inflation. For 2020, the threshold for the 28% bracket increased by $3,100 for all filing statuses except married filing separately, which increased by half that amount.

The AMT exemptions and exemption phaseouts are also indexed. The exemption amounts for 2020 are $72,900 for singles and heads of households and $113,400 for joint filers, increasing by $1,200 and $1,700, respectively, over 2019 amounts. The inflation-adjusted phaseout ranges for 2020 are $518,400–$810,000 (singles and heads of households) and $1,036,800–$1,490,400 (joint filers). Amounts for separate filers are half of those for joint filers.

Education and Child-Related Breaks

The maximum benefits of various education- and child-related breaks generally remain the same for 2020. But most of these breaks are limited based on a taxpayer’s modified adjusted gross income (MAGI). Taxpayers whose MAGIs are within the applicable phaseout range are eligible for a partial break — and breaks are eliminated for those whose MAGIs exceed the top of the range.

The MAGI phaseout ranges generally remain the same or increase modestly for 2020, depending on the break. For example:

The American Opportunity Credit. The MAGI phaseout ranges for this education credit (maximum $2,500 per eligible student) remain the same for 2020: $160,000–$180,000 for joint filers and $80,000–$90,000 for other filers.

The Lifetime Learning Credit. The MAGI phaseout ranges for this education credit (maximum $2,000 per tax return) increase for 2020. They’re $118,000–$138,000 for joint filers and $59,000–$69,000 for other filers — up $2,000 for joint filers and $1,000 for others.

The Adoption Credit. The MAGI phaseout ranges for eligible taxpayers adopting a child will also increase for 2020 — by $3,360 to $214,520–$254,520 for joint, head-of-household and single filers. The maximum credit increases by $220, to $14,300 for 2020.

(Note: Married couples filing separately generally aren’t eligible for these credits.)

These are only some of the education- and child-related breaks that may benefit you. Keep in mind that, if your MAGI is too high for you to qualify for a break for your child’s education, your child might be eligible to claim one on his or her tax return.

Gift and Estate Taxes

The unified gift and estate tax exemption and the generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax exemption are both adjusted annually for inflation. For 2020, the amount is $11.58 million (up from $11.40 million for 2019).

The annual gift tax exclusion remains at $15,000 for 2020. It’s adjusted only in $1,000 increments, so it typically increases only every few years. (It increased to $15,000 in 2018.)

Retirement Plans

Not all of the retirement-plan-related limits increase for 2020. Thus, you may have limited opportunities to increase your retirement savings if you’ve already been contributing the maximum amount allowed:

Your MAGI may reduce or even eliminate your ability to take advantage of IRAs. Fortunately, IRA-related MAGI phaseout range limits all will increase for 2020:

Traditional IRAs. MAGI phaseout ranges apply to the deductibility of contributions if a taxpayer (or his or her spouse) participates in an employer-sponsored retirement plan:

- For married taxpayers filing jointly, the phaseout range is specific to each spouse based on whether he or she is a participant in an employer-sponsored plan:

- For a spouse who participates, the 2020 phaseout range limits increase by $1,000, to $104,000–$124,000.

- For a spouse who doesn’t participate, the 2020 phaseout range limits increase by $3,000, to $196,000–$206,000.

- For single and head-of-household taxpayers participating in an employer-sponsored plan, the 2020 phaseout range limits increase by $1,000, to $65,000–$75,000.

Taxpayers with MAGIs within the applicable range can deduct a partial contribution; those with MAGIs exceeding the applicable range can’t deduct any IRA contribution.

But a taxpayer whose deduction is reduced or eliminated can make nondeductible traditional IRA contributions. The $6,000 contribution limit (plus $1,000 catch-up if applicable and reduced by any Roth IRA contributions) still applies. Nondeductible traditional IRA contributions may be beneficial if your MAGI is also too high for you to contribute (or fully contribute) to a Roth IRA.

Roth IRAs. Whether you participate in an employer-sponsored plan doesn’t affect your ability to contribute to a Roth IRA, but MAGI limits may reduce or eliminate your ability to contribute:

- For married taxpayers filing jointly, the 2019 phaseout range limits increase by $3,000, to $196,000–$206,000.

- For single and head-of-household taxpayers, the 2019 phaseout range limits increase by $2,000, to $124,000–$139,000.

You can make a partial contribution if your MAGI falls within the applicable range, but no contribution if it exceeds the top of the range.

(Note: Married taxpayers filing separately are subject to much lower phase out ranges for both traditional and Roth IRAs.)

Crunching the Numbers

With the 2020 cost-of-living adjustment amounts inching slightly higher than 2019 amounts, it’s important to understand how they might affect your tax and financial situation. We’d be happy to help crunch the numbers and explain the best tax-saving strategies to implement based on the 2020 numbers.

The future of tax planning is uncertain — even without dramatic change in Washington, D.C., many of the most significant TCJA provisions are set to expire within six years. Contact us for help with your year-end tax planning.

© 2019

---

The information contained in the Knowledge Center is intended solely to provide general guidance on matters of interest for the personal use of the reader, who accepts full responsibility for its use. In no event will CST or its partners, employees or agents, be liable to you or anyone else for any decision made or action taken in reliance on the information in this Knowledge Center or for any consequential, special or similar damages, even if advised of the possibility of such damages.